Black Space and Equilibrium

In a gallery in Perugia: one color, two artists, and 500 years of "now"

Cari amici,

One of my goals for 2024 is to get off my butt and see more of the tremendous array of art that’s part of the fiber of Italy. Though I love to spend entire days wandering through the mega-museums of Firenze and Roma and other major cities, there are plenty of wonders to be found in smaller venues, some of them very close to home. Such was the case for a show I went to called “NERO Perugino e Burri.” The show is a dialogue between Umbria’s two rockstar artists, Renaissance painter Pietro Vannucci, better known as Perugino (ca. 1450–1523), and contemporary artist Alberto Burri (1915–1995). The unifying thread of that dialogue? Their use of the color black.

Typically, Renaissance-era artists placed their Madonnas and saints and Christ figures in detailed landscapes or interiors; Perugino, on the other hand, broke convention by setting his figures afloat in a sea of black. The resulting stark contrast makes colors pop and details shine. In fact, it was from his Madonna and Child and Two Cherubim, whose greens, reds, and flesh tones shimmer against a black and dark brown background, that the idea for “NERO” was born.

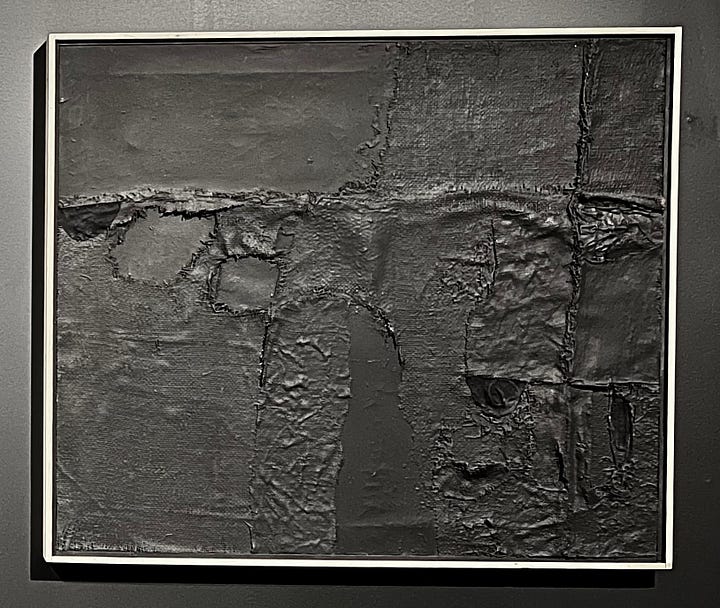

For Burri, who used black pigment extensively in his works, black signifies “not the absence of color but a darkness that allows light to emerge,” according to Fondazione Perugia. The same could be said about the show itself, held at Perugia’s Palazzo Baldeschi, whose spectacularly frescoed glory was obscured for the exhibit. How fitting, for a show centered on the idea of black space, to let viewers wander the rooms in semi-darkness. Each gallery held only two to four artworks, each one mounted on a tall black panel, creating a velvety space broken only by unexpected spots of bright, contrasting beauty.

So, A+ to the curators for the viewing experience, but what about the show itself? I’d wanted to see “NERO” mostly because I was curious about its concept, not because of the two particular artists placed in conversation. Burri’s work is extremely abstract, and I gravitate toward figurative art; and though Renaissance art is absolutely my thing, I’m not Perugino’s biggest fan. But this show included several Perugino works I hadn’t seen—one from the Louvre and two from a private collection, all of which inched him up higher on my list of favorite artists.

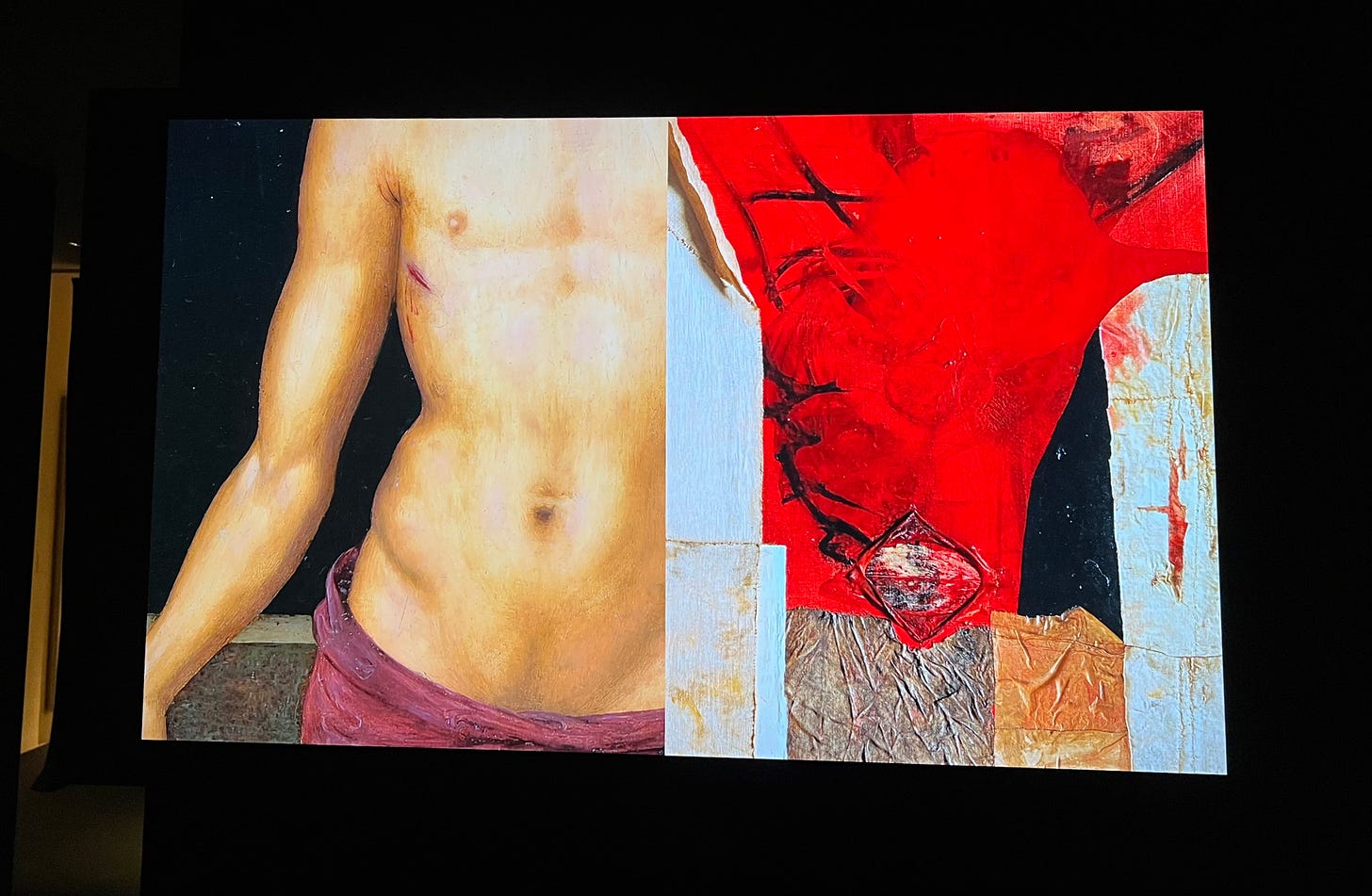

Expanding one’s awareness of an artist’s body of work is all well and good, but that was hardly the point of the exhibit’s loftier motives of black space and time and artistic connections. I won’t claim to understand fully the choices behind the pairings of the paintings; fortunately, a slide show at the end juxtaposed details of the paired works, which helped me grasp at least hints of the connections the curators saw.

Though I didn’t make all the curators’ connections, I did come away from the show with a new appreciation of both artists, and I’ll surely pay more attention to other artists’ ways of using black. And that’s good, but is it enough?

What’s the point of looking at art? Is it to admire beauty or marvel at technique? Is it to understand better the times the artist lived in, or something of their environments? In “realistic” paintings or sketches we see a particular landscape, or a typical Renaissance bedroom, or the defensive existence of a medieval town—all glimpses into a time machine made of pigment and form, subject and perspective, canvas and board. Nothing wrong with any of that. I’m guilty of seeking beauty, of preferring art that matches my aesthetic taste—Botticelli! Gentileschi! Bonnard! Sargent! Van Gogh!—not that it’s a sin to indulge in what gives me that burst of dopamine. Pleasure comes not just from that dopamine jolt but also from our emotional responses to certain images, colors, compositions, juxtapositions. Or we might get teary simply because an artist does something we think is impossible for ourselves. Even when we’re being analytical or historical minded, art can sneak in and elevate us, transport us out of our safe little worlds. But often that happens despite ourselves.

What if we push beyond our preferences or defaults? What happens then? And how do we manage to let go of our boundaries? How do we look at art, and how does the how affect our artistic preferences? What I discovered in the darkened rooms of “NERO,” in trying to understand the pairings of, say, a portrait of Christ with a deeply textured red canvas lacking any human figure, is that I succeeded best when I turned off my analytic brain. I’ve done it before—and written about it before—but I always have to remind myself to do it. In this case, if I stood across the room and focused on what I felt from those two pieces of art, what emotion or sensibility they evoked, both individually and together, especially in their use of black, I could begin to see a kind of reverberation between them. Between the two of them, one conversation; between the two of them and me, a different one.

Several days later I read a comment by Bruno Corà, the Baldeschi’s director and the co-curator, with art historian Vittoria Garibaldi, of “NERO,” in which he said part of what the show illuminates is “the concept of the space and that of the equilibrium of the works.” Maybe that equilibrium is what I felt. Maybe that was the core of the dialogue between artists separated by centuries.

“All art is contemporary. Because it is we who benefit from it.”

In retrospect, thinking about equilibrium gives added meaning to a quote posted at the exhibit’s exit: “All art is contemporary. Because it is we who benefit from it.” True, and a good rationale for the show’s pairing of two artists who lived centuries apart.

It’s those last few words—“benefit from it”—that resonate with me. I wish our tech- and science-focused world, our confused societies that suffer from information and disinformation overload and don’t know the difference, who think the pathetic imitative performances of AI are as good as human creations—I wish they recognized the benefits of art, of all kinds, from antiquity to today, whether it’s painting, sculpture, theater, writing, film, photography, and on and on. Art is part of our day-to-day equilibrium, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Maybe you don’t agree. But try to imagine a world without art, where only function matters. We’re programmed, if we give ourselves the time and freedom to do so, to recognize the splendor, the godliness, of creativity, to react in our hearts and guts to what we see as superhuman achievement. That’s what we’re doing when we say “Look at that!” or “Imagine making that!” That’s what we’re doing when we buy something of beauty and hang it on our walls—we’re finding joy, beauty, inspiration, delight. We’re finding equilibrium in an unsettled world.

Tante belle cose. Alla prossima—

Cheryl

Books of the week:

The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World by Paul Fisher (recommended by my friend Bridget Quinn, author of the next book listed, which is utterly fab)

Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order) by Bridget Quinn

Pietro Perugino by Joseph Antenucci Becherer

P.S. My book! Which you can buy here or on the usual sites, or, better yet, order it from your local bookstore. Another fab option is to ask your library to stock it. If you read it and like it, please tell your friends and/or leave a few lines of praise on any bookish site. You’d be surprised how much a rating or review helps authors. Baci!

Show looks fascinating! I feel like Italian curators are doing some very interesting things juxtaposing the older classic works from Ancient Rome, medieval and Renaissance with more modern works or even things drawn from the fashion and design world, like the Azzedine Alaia show at the Villa Borghese a few years ago. Thanks for highlighting this show and for your engaging commentary!