If you’re a Dante Alighieri fan, a train aficionado, or if you groove on medieval towns and mosaics, then hop on the Treno di Dante for a jaunt from Florence to Ravenna. This “slow tourism” idea began in 2021, to celebrate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death; however, the Treno di Dante ran between Faenza and Florence for at least five years before that. The current route traces the footsteps of the writer, philosopher, and political theorist from Florence across the mountains to Ravenna after his exile in 1302.

A friend and I hopped aboard on a Saturday (Dante, making the mountain passage on foot, would have been envious), snagging last-minute seats available only because a large group had a few cancellations. Book early!

The train

The Centoporte, so-called because it has 100 doors, was modeled on a 19th-century stagecoach and is, according to the Treno di Dante site, considered an icon of Italian railway history. These steam-engine trains ran until 1980; now, the few that are left hit the rails only for special events (sans steam engine).

We were in third class, where four of us sat in pairs, facing each other on wooden bench seats. They were pretty comfortable, but if you want more than bare wood, spring for a second class compartment with leather bench seats; fork out more for first class and that compartment will come with velvet-upholstered armchairs. Back in the day, there were pullout beds in first class, and everybody stayed cozy due to radiators tucked beneath the seats, fed by a central caldaia (boiler), or maybe several.

My favorite fun fact about this train is that initially it didn’t actually stop at the stations. You read right. It would slow enough for people to jump on or off—like a streetcar in San Francisco, one attendant said when I asked if I’d understood her correctly. (How I pity, and admire, any woman who made that leap in a pegged skirt.) Later, someone decided that wasn’t the best idea, and then the trains did come to a full stop. I’m not sure about this, but the change may have come about once the trains were used to deliver mail and merchandise, maybe because having letters and postcards flying about instead of making it to their destinations seemed, oh, I don’t know, sub-optimal. Or, who knows, maybe too many people had face-planted.

In addition to the passenger cars, each of which seats 60, the train has three specialty carriages. (Four if you count the hospital cars used during WWII.) My favorite one, the bagagliaio, or baggage car (now outfitted with bicycle racks for touring groups), is another an example of extremely questionable judgment, like the not-stopping-at-stations thing. Aong with baggage, the car also transported—wait for it—large animals. Because yeah, it makes perfect sense to let horses or other critters do their business on someone’s fine leather luggage. I mean, what was going on with the guy making these decisions? Was he high or what?

Another speciality carriage was the postale car, complete with official postal service workers, bins for each city and town’s mail, and, in the passageway outside, a handy-dandy mail slot. The doors and windows are barred because it wasn’t uncommon for looters to try to board trains and escape with the goods. Made me think of old Western movies with the bad guys sporting six-shooters and bandannas tied over their noses and mouths.

The third carriage contained yet another example of inane decision making. Along with a good-size safe, it held a not-so-good-size compartment for small animals, which, apparently, were all shoved in there together—dogs, cats, or whatever animal was fashionable at the time. Um, hello?

This car was also sort of pseudo-post office (no postal workers, only train employees), where you could do some unofficial post office stuff (buy stamps, maybe?). I’m not sure why this was needed when there was, you know, a regular post office next door, but I suppose they had their reasons. (Maybe there wasn’t always a postal car; I should have asked.) Anyway, the brakeman was stationed here, at a large brake control wheel. He wasn’t entirely on his own, though—for safety, each car has an emergency hand brake, and apparently sometimes they’d put a man on each brake so the train could glide to a super-smooth stop. (I don’t know when or why they’d do this. Listen, if you ever take this train, please ask all the questions I neglected and get back to me, k?)

The route

Treno di Dante follows a route through the Tuscan/Romagnan Apennines that opened in 1893. The 136-kilometer, three-hour trip traverses countryside dotted with small towns, plus two large parks, Parco Regionale della Vena del Gesso Romagnola and Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, and a handful of towns that Dante might have stopped at (and probably did). Here they are:

Borgo San Lorenzo: a medieval town with a fortress built by the ruling family to help control territory in foothills of the Apennines.

Marradi: a popular stop for wayfarers since Roman days, famous for its spring water. There’s a saying that if you drink the water there, you’ll have to return.

Brisighella: dominated by three mountain peaks, one with a fortress, one with a clock tower, and one with a sanctuary.

Faenza: a name that’s become synonymous with ceramics (faience in English, faïance in French). Along with the Museo Internazionale della Ceramica, you’ll find more than 60 ceramics workshops.

Once in Ravenna, travelers have four or five hours to explore the town, visit Museo Dante (interesting but odd; made me think of a carnival funhouse) and Casa Dante (a small, two-room museum), and gawk at the exquisite mosaics.

The Saturday trains stop for a little more than an hour in either Brisighella or Faenza. (The Sunday trains don’t stop.) Though we enjoyed seeing Brisighella, that gave us only four hours in Ravenna, and four hours aren’t enough. Having taken a 6:40am train from Perugia to Florence, then jumped on the 8:50 Treno di Dante, we were hungry, but given our limited time in Ravenna, we made do with a quick sandwich for lunch. A better idea (especially since our return train to Perugia was delayed by half an hour, getting us home around 1:00am) would be to take the Treno di Dante one way and spend a night or two in Ravenna. Next time!

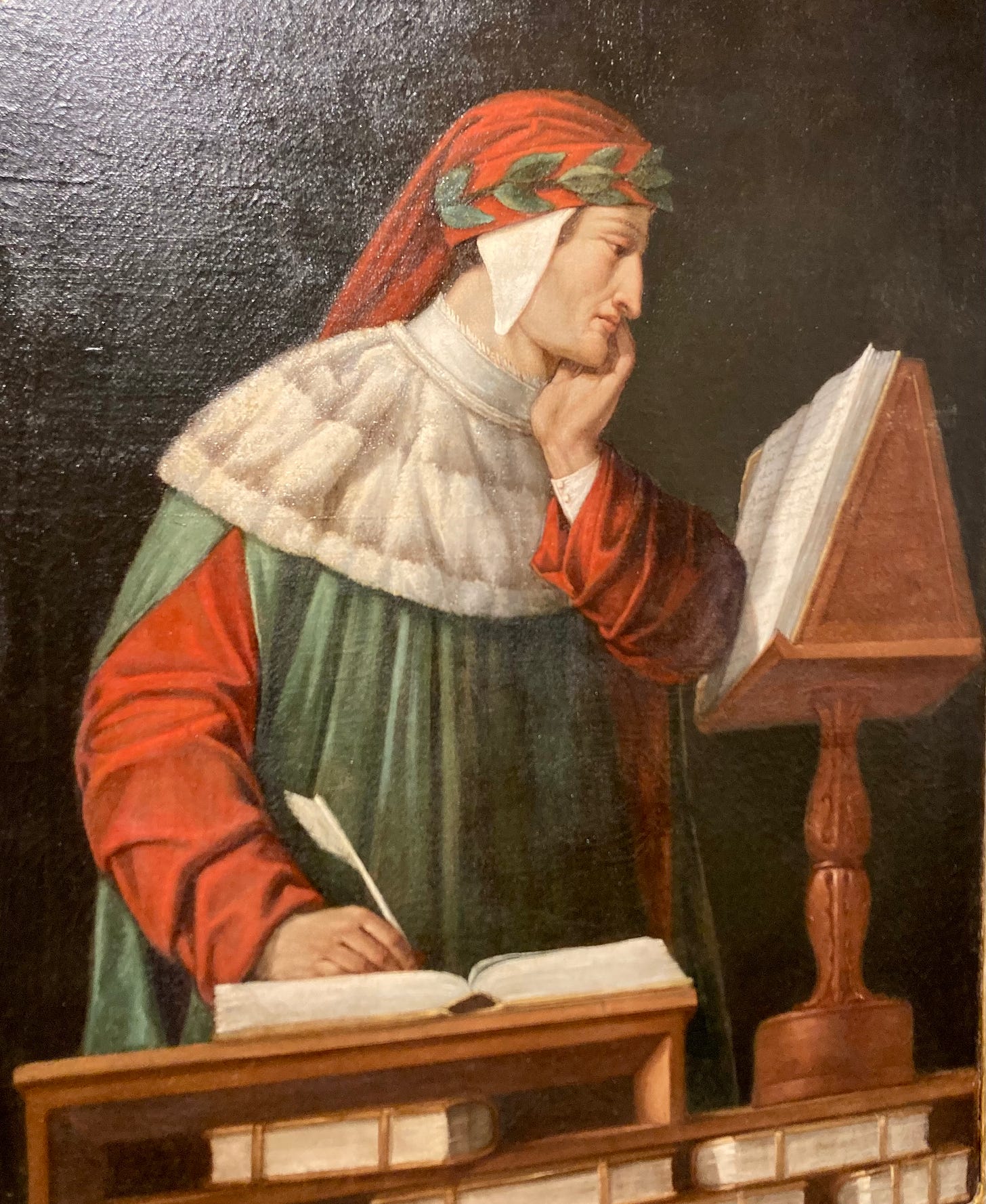

The poet

Dante Alighieri’s name is recognizable to plenty of folks who’ve never read The Divine Comedy or know much about the man himself. And, in fact, no one knows all that much, despite the hundreds of books written about him and his works. According to Museo Dante, there are few documents pertaining to his life, and we have not a single word written in his own hand. “Entire areas of his existence are inaccessible,” the Museo says. Most of what we know about him comes through his own work, in the descriptions of people and places he mentions or fictionalizes in his writings, and through his philosophical and political reflections.

So who was Dante? Here’s a nutshell answer, but I encourage you to read up on him, because he was a pretty complex guy.

Born in Florence in 1265, Dante was a writer of prose as well as poetry, an intellectual, and a political activist as well as a theorist. Medieval “Italy” (it didn’t become a nation until 1861) was characterized by political unrest, for centuries a tug-of-war between popes and emperors. At first Dante supported papal rule; later, he became “one of the most fervently outspoken defenders of the position that the empire does not derive its political authority from the pope.” (I’m leaving out all the stuff about the conflict between the Guelfs—of which Dante was one—and the Ghibellines, and later, between the Black Guelfs and White Guelfs—but again, it’s worth reading about.)

In 1302, Dante was summoned back to Florence from Rome, and when he failed to appear, he was sentenced to death for crimes he had not committed. He went into exile, traveling on foot north through the Apennines, and, toward the end of his life, ended up in Ravenna, on the Adriatic coast. There he wrote the “Paradiso” portion of La Commedia (Dante’s title; later the “Divina” was added), and there he died, in 1321, of malaria contracted in his travels to Venice.

Dante is, as you probably know, considered the father of the Italian language. He wrote La Commedia not in Latin, as was the norm, but in a vernacular based on the Florentine dialect, which evolved into what is now standard Italian. He also wrote Vita Nuova (New Life), De Vulgari Eloquentia (Eloquence in the Vernacular Tongue), Convivio (The Banquet), and De Monorchia (On Monarchy).

Dante’s ties to Florence were deep, yet he is buried in Ravenna, a city he lived in only briefly. The two cities have feuded for centuries over the poet’s resting place—a misnomer if ever I heard one, because the poor guy’s bones have been transient as heck. Florence, determined to reclaim her native son even though she would have offed him previously) made three attempts to do so, in 1396, 1429, and 1519, all of which (obviously) failed. Prior to the 1519 attempt, when a papal delegation arrived to take back the bones, they were gone—monks had removed them from the tomb and hidden them first inside a wall, then in the cloister, where they remained, forgotten, until 1677.

In 1781, Dante’s remains were moved to a new tomb built near the Chiesa di San Francesco, where they stayed until 1810, when Napoleon suppressed all religious orders, leading monks to hide them underneath a doorway in Chiesa di San Francesco. Forgotten, there they stayed until 1865, when they were discovered during church renovations and returned to the “new” tomb. Then came World War II, and once again Dante’s bones were on the move, this time to a nearby garden for safekeeping from bombs and looters. Now back in his proper place since December 1945, Dante is finally at rest.

Dante may be at peace, but Florence is still fuming. Stubbornly optimistic that one day Dante would return home, the city built a tomb for him in the Basilica di Santa Croce. But while tourists can visit the tombs of Galileo and Michelangelo there, they’re looking at only a stand-in for Dante. (Grudgingly admitting the great poet isn’t actually there, Florence inscribed the tomb to say that it only honors him.)

Florence is determined to keep its claim to Dante alive, though. Each year, on the anniversary of Dante’s death, the city provides Ravenna with enough oil to keep the votive lamp inside the tomb burning nonstop. (For a more detailed account of the Dante’s resting place feud between Florence and Ravenna, read this article in The Florentine, where I got most of my information.)

After sprinting through Ravenna, we left Dante to his eternal sleep and hopped back on board our train. Dusk fell as we sped toward Florence. I stood next to the windows—open wide enough that I could have leaned out—watching the night sky, inhaling the rush of cool air. An exhilarating sense of freedom on this wood-trimmed beauty, a piece of railway history hurtling into the night.

Books/poems of the week (they’re doing double duty this week):

The Divine Comedy: I really like the English translation by Allen Mandelbaum, but for a version in both English and Italian the most recommended one is the three-book set translated by Robert M. Durling and Ronald L. Martinez. Though the translation is more precise than Mandelbaum’s, the language is much less lyrical. I recommend reading Dante out loud, by the way, so that you don’t gloss over a single syllable.

La Vita Nuova, translated by Barbara Reynolds. Apparently this is the translation to buy (and I just did) of this series of love poems (Dante’s for Beatrice) and his own prose commentary on the poems.

Fantastic!! I had never heard of this train and MUST take it sometime!! And while I’ve read about the circumstances around his exile and death, I knew nothing about the- shall we say, comedy of his remains. I so appreciate this piece and will share with my grad school friends and Dante professor!

Beautiful....love old train journeys. Thank you for sharing this in such depth <3